Albania has appointed an artificial-intelligence system as a cabinet-level minister to oversee public procurement, a move the government says is designed to remove human discretion from the awarding of state contracts.

Prime Minister Edi Rama introduced the AI bot, named “Diella” — Albanian for “sun” — while unveiling his new cabinet on Thursday as he prepares to begin a fourth term.

Rama said Diella will manage and award all government tenders, a sphere long marred by corruption allegations in the Balkan state. He described Diella as Albania’s first virtual cabinet member, adding that the aim is to ensure tenders are “100% free of corruption”. The government did not publish technical details on governance, audit trails or human oversight for the system.

The appointment follows Albania’s May parliamentary election, which left Rama’s Socialist Party on course for an unprecedented fourth term. Procurement reform featured prominently in his campaign alongside a target of securing European Union membership by 2030 — a timetable analysts have called ambitious. Persistent concerns over graft have weighed on accession progress.

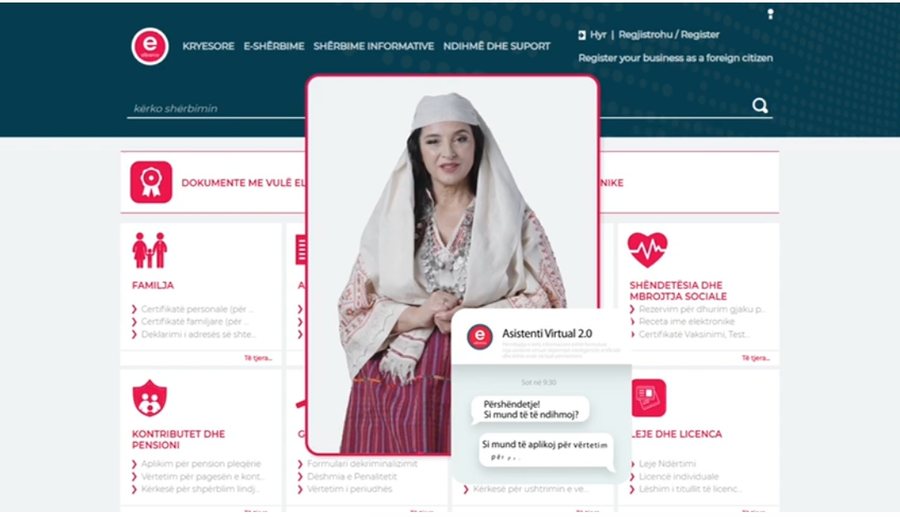

Diella is not entirely new to Albanian users. Earlier this year the government rolled out a virtual assistant under the same name on the e-Albania portal, providing real-time help to citizens and businesses seeking state documents and certificates. The assistant, presented with a digital avatar in traditional dress, supports voice queries and issues documents with electronic stamps. Thursday’s step elevates that assistant into a procurement-specific role at ministerial rank, consolidating responsibility for tendering decisions.

Public reaction has been mixed. Supporters argue that removing humans from the decision chain could cut opportunities for bribery, intimidation or favouritism. Others questioned whether an AI tool can be insulated from manipulation or biased inputs, and what recourse bidders would have to challenge automated decisions. The government has yet to outline security safeguards, red-team testing, or the mechanism for parliamentary and judicial scrutiny.

International and local observers have previously highlighted corruption risks in Albania’s procurement sector. In 2024, regional analysts cautioned that deploying AI in tendering is not a simple fix and depends on high-quality data, transparent criteria and independent oversight. Recent scrutiny of major waste-to-energy projects also underscored the sensitivity of large public contracts.

The government has framed Diella as a transparency tool. However, key implementation questions remain: which datasets will train and inform the model; how conflicts of interest, bid-rigging indicators and abnormally low bids will be detected; and whether the AI’s decision-making logic will be published or subject to external audit. Best practice in algorithmic procurement typically includes immutable logs, post-award disclosure, and clear appeal pathways for bidders — elements not yet detailed by Tirana.

Social media reaction on Thursday reflected scepticism as well as curiosity, with users suggesting that any failures might be blamed on the tool rather than human supervisors. The Prime Minister’s office did not immediately provide a timeline for full operational deployment, nor specify whether ministries and municipalities would cede all tendering authority to the centralised system from day one or via a phased transfer.

Albania’s new parliament, elected in May, is scheduled to convene on Friday. It was not immediately clear whether the government would face a confirmation vote the same day or later. Should Diella’s mandate be endorsed, its early test will be whether planned procurements — including in infrastructure and municipal services — proceed with faster timetables and fewer disputes, while meeting EU-aligned transparency standards.

The decision places Albania among the first governments to assign a core administrative function to an AI system with cabinet status. Other countries have experimented with algorithmic tools in procurement and service delivery, but few have formalised such roles at ministerial level. The extent to which Diella can reduce opportunities for misconduct will depend on data integrity, the design of scoring models, and the strength of external checks.