Boris Johnson’s warning this week about Europe’s Belgian-led capitulation to Kremlin intimidation should not be brushed aside as the familiar boom of a former prime minister seeking relevance.

His remarks strike at a deeper truth that too many European leaders would rather ignore: when confronted with a moment demanding courage, vision and moral clarity, the EU’s sprawling bureaucracy can be relied upon for only one thing — hesitation.

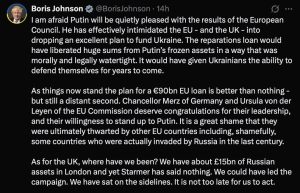

Johnson’s argument is stark. Vladimir Putin, he says, will be “quietly pleased” with the outcome of the European Council, which abandoned the boldest and most ethically coherent plan yet conceived to secure Ukraine’s future: a reparations-backed loan powered by frozen Russian assets. It was an ingenious mechanism, allowing the West to turn the Kremlin’s own money — money sitting idle as Russia levels Ukrainian cities — into long-term defence funding. Legally defensible, morally unimpeachable, economically transformative. The sort of idea Europe should have championed.

Instead, the EU recoiled. Having grandly declared that Ukraine’s defence was Europe’s fight, it found itself unable to muster the will to act when it mattered. One can hardly feign surprise. Expecting decisive leadership from an apparatus designed to avoid risk is a category error. Brussels is many things — committee-driven, process-obsessed, allergic to velocity — but it is not built for moments of moral confrontation. When unanimity is the price of progress, timidity becomes the system’s organising principle.

Nowhere has this been clearer than in Belgium’s behaviour. The country sits atop roughly €210 billion in immobilised Russian central bank assets — and the income generated by them — while searching for every procedural pretext to avoid releasing even a fraction to Ukraine.

The veto championed by Bart De Wever, the powerful figure behind Belgium’s governing coalition, has become emblematic of this paralysis. Whatever diplomatic gloss one tries to apply, the underlying motive is plain enough: self-interest. Belgium’s treasury benefits handsomely from hosting these assets. Ukrainian soldiers at the front do not.

It is perfectly legitimate for a sovereign state to weigh its own financial exposure. But let us not pretend that this is anything other than national advantage placed above European security, and above a nation fighting for survival. Belgium’s position may be lawful. It may be convenient. But principled it is not.

More dispiriting still is the behaviour of those EU countries whose own histories under Soviet rule ought to have stiffened their resolve. Instead, they muttered anxiously about “legal concerns”, knowing full well that the real anxieties lay elsewhere: Russian energy, domestic politics, the fear of retaliation. To watch nations scarred by Moscow’s past aggression shrink from confronting it now is not only ironic — it is tragic. It is pathetic.

The result? A limp, €90 billion EU loan package that is indeed, as Johnson says, “better than nothing”—yet still a pale substitute for what might have been. A bucket offered where a pump was needed.

Johnson is right to salute those who at least attempted to break the inertia. Ursula von der Leyen, whatever one thinks of her broader tenure, showed a clarity and boldness that stood out amid the fog. Germany’s new Chancellor, Friedrich Merz, similarly deserves credit. In just months he has displayed more strategic seriousness on Ukraine than his predecessor managed in years. But even their combined efforts could not drag a reluctant European Council across the finish line.

All of which makes Britain’s passivity even more puzzling. No longer shackled to EU unanimity, the UK could have seized the initiative and shaped the moral debate. With roughly £15 billion in Russian assets held in London, Britain was uniquely positioned to demonstrate what leadership looks like — to show allies that we still understand the responsibilities of a major power.

Yet Whitehall has been inert. Sir Keir Starmer, whose international posture so often aspires to statesmanlike gravitas, has been conspicuously mute on the question. His silence may be politically safe, but it is strategically shabby. At a moment when Europe was floundering, Britain could have acted. Instead it watched.

This is doubly frustrating because the moral and strategic case for repurposing frozen Russian assets is unanswerable. These funds are not incidental holdings. They are sovereign reserves belonging to a state that has launched a war of territorial conquest in Europe. If such aggression does not trigger the extraordinary use of impounded assets, what on earth would? If international law is to mean anything, it must allow for consequences.

Supporting Ukraine is not an act of charity. It is the defence of European security, of the credibility of Western alliances, and of the principle that borders cannot be erased by brute force. A victorious or merely unpunished Russia would embolden every authoritarian state watching from the wings — and there are many.

This is why Boris Johnson’s intervention matters. It exposes a transcontinental malaise: stirring rhetoric paired with shrinking resolve. The great pity is that Britain, once the West’s most reliable source of strategic candour, now appears content to loiter on the sidelines.

But as Johnson says, “It is not too late for us to act.” It is not. Britain can still legislate to deploy the frozen Russian assets within its jurisdiction. Doing so would shame Europe into rethinking its timidity, and it would send a message to Washington that someone on this continent still understands the stakes.

History remembers who showed courage — and who hid behind process. Britain still has time to choose the right side of that ledger – if only the country had a real leader.

Main Image: https://twitter.com/10DowningStreet/status/1220759626427310082

Click here for more News & Current Affairs at EU Today

Click here to check out EU TODAY’S SPORTS PAGE!

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________